From Wheels to Words: A Bushnell Building’s 150-Year Journey

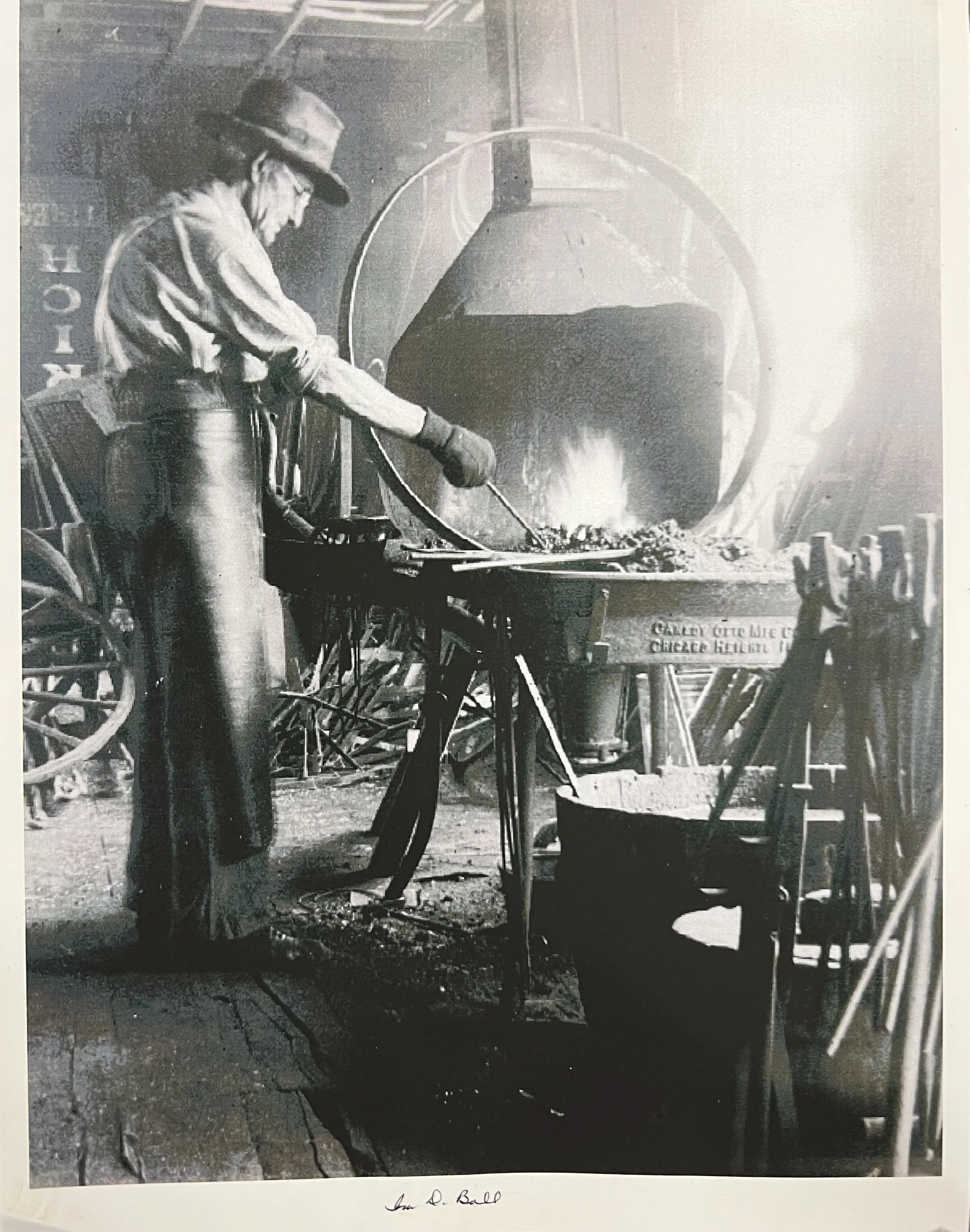

Ira D. Ball at work inside the Bushnell wagon manufactory, late 19th century.

Josiah Chatterton - The Forgottonia Times™

In the early days of Bushnell’s industrial rise, when prairie grass stretched to the horizon and the railroad was still a recent promise, a small wagon shop opened that would help shape the town’s economic future — and, more than a century later, give new life to the building that is now The Forgottonia Times office

In 1863, Ira D. Ball came to Bushnell and entered the wagon manufacturing industry, sewing together the practical needs of Civil War America with the enterprising spirit of the Midwest. A native of New Jersey, Ball had learned the trade of carriage and wagon making, and when he set up shop beside the burgeoning rail lines, his business continued to grow.

Not long after opening, Ball’s sons joined him in the enterprise, and by the time the family operation took on the name Ball and Sons’ carriage and wagon manufactory, it had become one of the primary industrial institutions in Bushnell.

Carriages, Buggies, and Hard-Working Hands

Historical records from a comprehensive 1885 industrial survey paint a vivid picture of the factory’s operation. At that time, sources report that Ball and Sons not only carried a large stock of carriages and wagons, but had built two 28-by-48-foot, two-story repositories, each with its own blacksmith and wagon shop in back.

Manufacturing operations on the premises, likely in the rear work area of the property.

These premises weren’t just for show. According to that same 1885 industrial survey — written at a time when communities often highlighted their most successful local enterprises — the business employed about a dozen workers during the busy season and produced an average of about 100 buggies per year, a respectable output for a specialized rural manufacturer in the late 19th century.

That production scale — a team of skilled craftsmen turning out high-quality vehicles by hand and hammer — served farmers, families, and local businesses across west-central Illinois. According to David Sneed, a respected historian of wagons and horse-drawn transportation and founder of Wheels That Won the West, Ball & Son’s operation was a cut above the level of a typical corner blacksmith shop.

“In the 1904 American Carriage & Wagon Directory, Ball & Son is shown as the largest wagon maker in Bushnell, with a reported net worth of at least $10,000,” Sneed explained in an interview with The Forgottonia Times. “That kind of operation is well beyond a shop that might make a wagon or two a year. My feeling is that Ball & Son had grown to be a good-sized local and regional maker.”

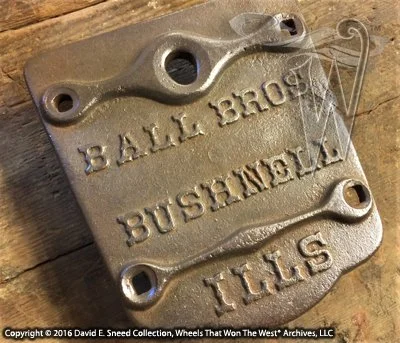

Sneed noted that transportation was just as essential in the late 19th century as it is today. “The agricultural atmosphere and need for hauling goods and raw materials, as well as requirements for personal travel, created tremendous opportunity for those skilled in wainwright, wheelwright, and blacksmithing abilities,” he said. “The fact that Ball & Sons had the means to have a custom reach plate designed for their wagons tells me they were a good-sized regional maker. Smaller builders would have just purchased generic plates and been satisfied with identifying their wagons with only painted logos.”

This custom reach plate offers a rare physical link to the Ball Bros. operation, preserving the company’s name in iron more than a century later. Courtesy of Wheels That Won The West® Archives, wheelsthatwonthewest.com

As the enterprise grew, so did its reputation within the trade and the region it served. A 1907 biographical sketch of Ira D. Ball describes the company, operating under the name “Ball Brothers,” as “one of the most extensive and thoroughly equipped of its kind in the country,” reflecting how the firm was viewed by contemporaries at the height of its operation.

End of an Era — and A New Beginning

After nearly half a century in business, Ball Bros. remained active in Bushnell’s industrial life into the early 20th century before closing around 1914.

What happened next reflects the dramatic technological shift sweeping America at that time. As horse-drawn carriages gave way to motor vehicles, the very building that once turned out wagons and buggies found a new industrial purpose.

After Ball Bros. ceased operations, the building was reused for automotive purposes, including a period in which it housed a Packard automobile dealership. This shift mirrored a broader regional transition as facilities once devoted to horse-drawn transportation were adapted for the emerging automobile age.

The former Ball Bros. manufactory after its repurposing as a Packard automobile dealership, mid-20th century.

This transition — from crafting vehicles pulled by horses, to selling machines powered by internal combustion engines — illustrates Bushnell’s ability to adapt. Sneed notes that this kind of repurposing was common across the country as America entered the automobile age. “It’s not overly surprising to hear of a building being repurposed,” he said. “The same kinds of things happen today.”

He pointed to examples ranging from former hardware stores that once sold wagons and carriages, later becoming banks, to the Flint Wagon Works in Flint, Michigan, which shifted from building wagons to producing some of the first Chevrolet and Buick automobiles in the United States.

For Sneed, the deeper significance of these transitions lies not just in changing technology but in continuity of purpose. “It’s a rich background deeply related to the spirit of American capitalism; the freedom to pursue a destiny and the opportunity to realize dreams,” he said. “Knowing that history can be extremely encouraging and personally rewarding. It’s the same reason so many still see America as the Land of Opportunity today.”

Packard automobiles on display inside the former carriage manufactory, framed by patriotic symbols that reflected both national pride and the promise of modern travel.

A Modern Twist on Manufacturing

Fast forward more than a century, and the building that once rang with hammer blows and wheel spokes now houses Midwest Control Products, a company that began operations in 1967 and continues to operate manufacturing facilities in Bushnell today.

This continuity of industrial use — from horse-drawn carriages to modern components — highlights Bushnell’s long-standing role in production and innovation. Midwest Control Products’ presence underscores how the community’s manufacturing roots have endured through decades of technological change.

And for the past few years, the building has served yet another vital role: as the home of The Forgottonia Times newspaper, where local history is documented, celebrated, and shared with readers across the region.

Why This Building Matters

Today, residents walking past our office might see only a familiar local landmark. But beneath its bricks and beams lies a story of American ingenuity: a place where men and women built essential tools for daily life, adapted to profound changes in technology, and now house a modern manufacturing facility alongside a community newspaper.

It’s a physical reminder that history doesn’t just live in old photos or dusty archives — it’s woven into the places we inhabit every day. And as we publish this story from within its walls, we are reminded that every building has a past, and every past has a story worth telling.