A Better Way to Get to Church: Forgottonia and the Birth of the Automobile

By - Harry Bulkeley

"Whoa!" Caleb pulled on the reins and brought the carriage to a halt. Bessie took the kids inside while he unhitched the horse and led it back into the barn. After feeding and mucking the stall, Caleb pulled the carriage inside for the next trip. The whole time, he was wishing there was an easier way to take the family to church.

Man has been tinkering at least since the time that Fred Flintstone asked Barney Rubble to come over and help him fix his stone car. In the 19th century, men like Caleb started tinkering in their barns and garages, trying to find some way to make a carriage move without a horse.

This was at a time when engines were becoming available by mail order, and tinkerers started playing with ways to make an engine turn the wheels.

We usually think of Detroit when we talk about the early auto industry, but it was going on everywhere, including right here in Forgottonia. Most people don't know that the Duryea brothers, who are generally credited with building the first car in America, were born in Canton (Fulton County) and Washburn (Woodford County), Illinois. They grew up in Wyoming in Stark County.

Though they were born here, they developed their car elsewhere. But there were lots of inventors who manufactured cars all around this area.

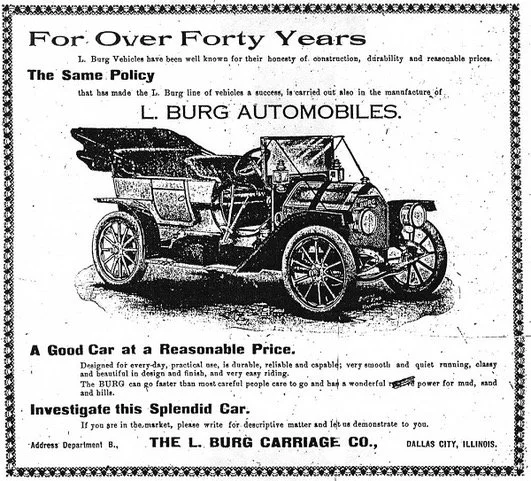

We've all heard names like Ford, Olds, and Buick, but there were other automotive pioneers who worked right here in Western Illinois. Take Louis Burg of Dallas City. He had owned a carriage company for several years before he started buying parts to make cars. By 1910, he was employing 40 people in his factory in Henderson County. Just up the road from Mr. Burg, they were making the Lomax Auto in, you guessed it, Lomax.

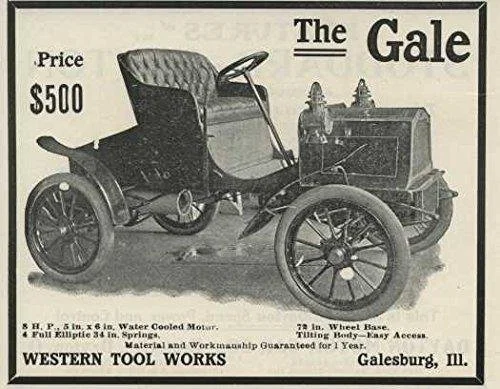

In Galesburg, they manufactured The Gale. It actually lasted for several years, and there are still a few of them in existence. An interesting feature was that the body was hinged at the rear, so to work on the engine, you lifted the whole body up and leaned it toward the back of the car.

Most of the early tinkerers didn't have a long run because they didn't have the capital to finance their ventures. One family that did have the money was the Deere family in Moline. Their first effort was called the Deere-Clark, but it only lasted a couple of years. John Deere's grandson, Willard Velie, developed and sold the Velie for almost twenty years. If cars weren't enough, the company also made airplanes.

The first question when you're turning a carriage into a car is what will power it? In the very early days, the choices were about evenly divided between gas, steam, and electric.

The problem with gas was that there weren't any gas stations where you could buy fuel. (Like charging stations today.) Lots of pioneers used steam, but lots of drivers were nervous about sitting on a pressurized boiler while driving. Electric cars were marketed to women because they did not require cranking to start them. They even had a range of 25 or 30 miles!

Once you got the thing moving, you had to invent a way to steer it, stop it, and drive it after dark. All those things took time and innovation, but eventually we arrived at today's cars.

Now, when I get in my car, it tells me if my door is shut, my seatbelt is fastened, and if there is anybody walking or driving behind me. It can actually tell if I'm getting sleepy!

So Caleb's wish to find a better way to take his family to church was finally realized, thanks, in part, to tinkerers right here in Forgottonia.